Nurse Sharks Dry Tortuga’s

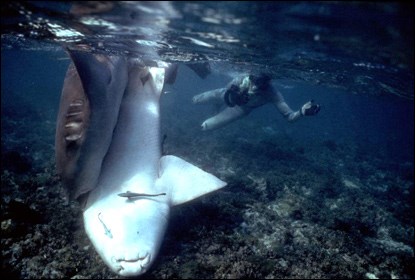

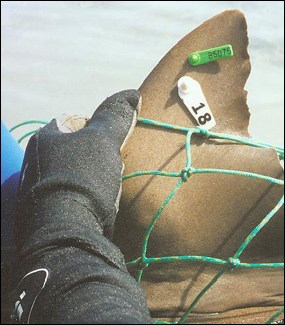

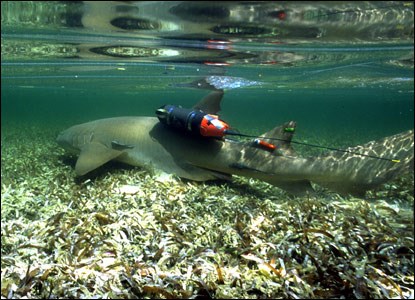

Wes Pratt, Mote Center for Shark Research Sharks range in lifestyle and demeanor from the fast, aggressive shortfin mako to the more relaxed and sedentary bottom dwelling sharks. Although all sharks are carnivorous, meaning they eat other animals, nurse sharks fall into a category of laid back, easy-going sharks that prefer to swim awhile and then rest awhile. Nurse sharks (Ginglymostoma cirratum) may in fact be considered the “couch potato” of the shark world. This label, however, is not meant to imply that their lives and behaviors are simple and always relaxed; quite the contrary! But they do slow down, swim locally, and associate — sometimes in cozy piles — with other similar-sized nurse sharks in the shallow warm seas they usually inhabit. Such behavior allows time for shark socializing and fosters the development of interesting group behaviors.  Wes Pratt, Mote Center for Shark Research Nurse sharks are typically found in tropical to subtropical waters in coral and rocky reefs, on grass and sponge flats, and among the roots of mangrove shorelines. In warm tropical waters, they are common, mostly nocturnal, inshore, bottom-living sharks. The range of nurse sharks in the Atlantic Ocean extends from Rhode Island to southern Brazil, including the entire Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. In the eastern Atlantic their range extends from the Cape Verde Islands to Gabon along the African coast. Their range along the American Pacific coast from extends from Baja California in Mexico to Peru. In general, their depth range extends from the intertidal zone down to a depth of at least 40 feet.  Wes Pratt, Mote Center for Shark Research Nurse sharks typically are born during the winter. They are about 1 foot in length at birth and grow 4 to 6 inches a year in length, less as they get larger. The time to reach adulthood and mating can be as long as 15 to 20 years, at which time they are 7 to 7.5 feet in total length. The maximum length recorded is 13 feet but no one has reliably measured a nurse shark longer than a bit over 9 feet. Although sharks are diminishing in number and the biggest ones are the hardest to catch, a few larger nurse sharks may still exist in remote areas as yet unnoticed by science.  Wes Pratt, Mote Center for Shark Research Nurse sharks are easily identified by the small mouth located forward of the eyes and just under the broad snout. The mouth is bracketed by two sensory barbels. Most nurse sharks range in color from light to dark brown, though rare albino nurse sharks also exist. Young nurse sharks have little black spots along their backs. The ventral surface (belly) is a creamy white. The teeth are small but exceedingly sharp and, like the teeth of all sharks, are replaced by moving slowly forward as if they were on a conveyor belt. Older teeth slough off while the shark feeds and are replaced by sharper, slightly larger teeth.  Wes Pratt, Mote Center for Shark Research The success of nurse sharks as a species results in part from a wide diet of fish and reef invertebrates, caught mostly at night by suction feeding in crevices. Young nurse sharks will patrol the flats day or night on a rising tide in search of foraging crabs and octopi. They hunt by brushing the bottom with the two oral barbels, often twisting back to lunge head first into the bottom in pursuit of prey. Water is powerfully sucked in through the mouth, with silt and sand puffing out of the gills as the tail slaps the surface. The shark’s tough hide and smooth tile-like scales keep damage from impact to a minimum. Crabs, shrimps of all kinds, and lobsters are taken whole from under the reef. Nurse sharks will often snap the lobster’s head off with a shake, consuming the tail immediately. Small conch also are a favorite; the sharks use their powerful jaws to break open the shells.  Wes Pratt, Mote Center for Shark Research Knowingly or not, people swim near nurse sharks every day without incident. Attacks on humans are rare but not unknown and a clamping bite typically results from a diver or fisherman antagonizing the shark with hook, spear, net, or hand. The bite reflex is such that it may be some minutes before a quietly re-immersed nurse shark will relax and release its tormenter. The small teeth seldom penetrate deeply but are razor sharp. Holding still reduces damage to both shark and man. Leaving sharks alone is the best tactic. Nurse sharks were caught in directed fisheries in the 1940s for their hides (shark leather) and liver oil and killed as by-catch in long lining and trap and net fisheries. They are regarded as too sluggish for sport fishing and are undesirable for food or the fin trade. The flesh of sharks and other long-lived fish species concentrates mercury and other toxins and should be avoided. Nurse sharks have been kept by aquarists and researchers as they are hardy, live a long time, and are quick learners. However, keeping them in home aquaria is not wise as they will eventually reach 9 feet long! They are more valuable to all of us alive and free in the ocean. More importantly, with the help of the nurse shark as an easily observed and studied species, we are learning the importance of sharks in tropical ecosystems. Their apex position in the ocean’s energy flow makes them equivalent to the lions and tigers of terrestrial systems. By studying the nurse and other shark species, we are just beginning to understand how the life history and activities of these sharks is important in balancing oceanic food webs and keeping coral reef ecology healthy and diverse. The Dry Tortugas Nurse Shark Project Wes Pratt, Adjunct Scientist  Theo Pratt, Mote Center for Shark Research The Dry Tortugas Nurse Shark Research Project (NSRP) was initiated in 1991 to understand and explore the fascinating world of shark reproductive behavior and population ecology. The project is a long-term cooperative study between Mote Marine Laboratory, Albion College, and Southern Illinois University of the island group’s population of nurse sharks. Such research is possible in this special place because nurse sharks are relatively mild-mannered and largely non-migratory. Many are born, forage, mate, and live out their lives in the Dry Tortugas area. Most other large shark species are highly migratory in nature with widespread populations that are always in danger of being caught or even extirpated by fisheries. Our studies focus on three topics of research:  Wes Pratt, Mote Center for Shark Research Population Dynamics To better understand shark distribution and daily and seasonal movements, we began tagging Dry Tortugas nurse sharks with fin tags in 1993. To learn about shark relatedness and possible family ties, a genetics component was added to the study in 1995. Tagging occurs every year during the June/July mating season. About 24 percent of tagged individuals are recaptured in subsequent years and changes in their length, weight, and reproductive condition add to our knowledge of their otherwise cryptic lives. We have net-recaptured some individuals in 7 different years and several adult females were recaptured 12 years after their initial capture. One adult male has been visually observed more than 60 times while courting females over several years.  Wes Pratt, Mote Center for Shark Research In addition to fin tags, we place long-lived acoustic coded electronic transmitters on selected adult sharks. These coded tags are detected year-round by fixed hydrophone listening stations. These stations can record tens of thousands of detection events every year. The combined tagging methods will eventually detail the distribution and seasonal movements of the tagged adults. We now know that some sharks call the Dry Tortugas home and spend much of their lives there, while others travel hundreds of miles and return seasonally to these islands to mate. Some females spend their months of pregnancy in the warm, protected waters of the area. Using the latest technology and old-fashioned on-site observation, we have learned much about seasonality, residency times, growth, and movements of juvenile and adult sharks.  Wes Pratt, Mote Center for Shark Research Behavior Observations of adult shark behaviors over the years have led to unexpected and unprecedented revelations about their social lives and complex reproductive behaviors such as female mate choice and male cooperation. These behaviors influence reproductive success and hence the future success of this important shark species. The Dry Tortugas population is ideally suited to behavioral studies because NSRP scientists can identify returning individuals by distinctive tags and observe how the sharks individually interact. Shark-borne video (National Geographic’s Crittercam) has been employed in the past and more recently temperature, depth, and movement loggers have been attached to adults to allow the documentation of shark activities not visible to observers. Dry Tortugas footage filmed by Wes was used by the Discovery Channel to produce “The Ultimate Guide to Sharks: Shark Mating.”  Wes Pratt, Mote Center for Shark Research Reproductive attempts observed in the wild generally involve one single male approaching a female that is resting or swimming. Males initiate mating by orally grasping or attempting to grasp the chosen female’s pectoral fin. Mating events involving solo males result in copulation 6.6 percent of the time. A small proportion of observed events involve multiple males. From three to at least ten males pursue a selected female, circle into position, and compete to grasp the female’s pectoral fins. If she cannot, or does not, choose to avoid contact, she is herded or physically carried by the males out of the shallows and into the channels (1-2 meters deep), where the water is deep enough to permit copulation. During this time, competition for a fin grasp, a necessary prelude for successful copulation, becomes intense. Males nudge, bump, and push each other as they vie for the unshakable oral grasp of the female’s pectoral fin that precedes and expedites copulation.  Wes Pratt, Mote Center for Shark Research Habitat Use Tagging with conventional and electronic tags also shows how nurse sharks use the various tropical ocean habitats available to them; for nurse sharks it is primarily the shallow flats, intermediate hard bottoms, and deeper coral bank reefs. Nurse sharks interact with habitat in a number of different ways: as foraging areas, mating and nursery grounds, and for environmental refuge.  Jeffrey Carrier, Albion College Individual sharks of all sizes from young-of-the-year to mating adults are in the study population, and this population and its vital habitat has been protected in the Dry Tortugas since 1996 by the closure of a small area that they use during their vulnerable reproductive times. All marine life is interwoven. Sharks are “apex predators” and occupy the highest level of oceanic trophic organization. To understand nurse shark habitat, behavior, and population dynamics is to add an important piece toward understanding the larger picture of all diverse shark species and how they fit into the panorama of tropical oceanic life. Such information is vital for humankind to responsibly manage, conserve, and enjoy these exciting and important ocean neighbors. |